A mail server to receive email

This tutorial covers how to set up a mail server to receive and send email. This part covers the technical details to enable receiving emails from others.0. Opening ports in Azure

To set up a mail server, you'll need to open specific ports to allow incoming and outgoing mail traffic. The ports you need to open depend on the email protocols you plan to use. The most common email protocols are SMTP (Simple Mail Transfer Protocol) for sending emails and IMAP (Internet Message Access Protocol) or POP3 (Post Office Protocol) for receiving emails. Here are the ports typically associated with these protocols:SMTP:

Port 25: This is the default port for SMTP. It's used for outgoing mail (sending emails).IMAP:

Port 143: This is the default port for IMAP, which is used for receiving emails. It's not secure and is typically used with STARTTLS or SSL/TLS encryption.Port 993: This is the secure IMAP port, which is used when IMAPS (IMAP over SSL/TLS) encryption is employed.

POP3:Port 110: This is the default port for POP3, used for receiving emails without encryption.

Port 995: This is the secure POP3 port, used when POP3S (POP3 over SSL/TLS) encryption is employed.In this tutorial, we only use SMTP and IMAP, so need to open the following ports:

- SMTP (inbound): Port 25, Port 587 for secure email submission by clients

- IMAP (inbound): Port 143, Port 993 (with SSL/TLS)

- SMTP (outbound): Port 25 (optional)

Go to Azure portal and open the above ports. Additionally, Open HTTP (inbound): Port 80 and HTTPS (inbound): Port 443 ports for web service.

1. Installation of software

We must install a series of software: pwgen (generates random password), MariaDB server (database management system), postfix (mail server), Apache and PHP (web server), rspamd (dealing with spam), swaks (test email delivery), and mutt (view email in command line). Additional software to store email is dovecot.

pwgen

Let’s start with the pwgen utility. It helps you create secure passwords. Unless you already have a tool for that…sudo apt install -y pwgen

You will need a random password later to create a database user for the mail server. Just as an example: to create a secure password having a length of 20 characters you would run:pwgen -s 20 1

That gets you a string like “W2EzNUFJzjEmA8tQT7A0”.MariaDB server

If you used MySQL before you may remember that you were forced to specify a password for the ‘root’ database user. That has changed with MariaDB in Debian – for the better. Now you can access the database server without any password if you are logged in as ‘root’ on the server. You might as well set a password but it is not necessary.Go install the MariaDB server package:

sudo apt install -y mariadb-server

If all went well you can now run “mysql” and get a connection to your MySQL database:

azureuser@md:~# sudo mysql

Welcome to the MariaDB monitor. Commands end with ; or \\g.

Your MariaDB connection id is 395

Server version: 10.5.29-MariaDB-0+deb11u1 Debian 11

Copyright (c) 2000, 2018, Oracle, MariaDB Corporation Ab and others.

Type 'help;' or 'h' for help. Type 'c' to clear the current input statement.

MariaDB [(none)]>

Exit the SQL shell by typing “exit” or pressing CTRL-D.

Postfix

Now on to the Postfix packages:sudo apt install postfix

sudo apt install postfix-mysql

Apache and PHP

To provide a webmail service you need the Apache web server software and the PHP scripting language support:sudo apt install -y apache2 php

swaks

A very useful tool to test email delivery later is SWAKS (the SWiss Army Knife for Smtp):sudo apt install -y swaks

mutt

This is a full-featured IMAP mail client. Think of it as the vi of mail clients. It cannot display HTML but it is very helpful to test IMAP mail servers. And some hardcore users still prefer it over any other mail client.sudo apt install -y mutt

Dovecot

In addition to Postfix (that handles SMTP communication) you will need Dovecot to store received emails and provide IMAP (and optionally POP3) access for your users:sudo apt install -y dovecot-mysql dovecot-pop3d dovecot-imapd dovecot-managesieved dovecot-lmtpd

Adminer

SQL databases are called like that because SQL (structured query language) is the way you talk to it. But as we are just puny humans let’s have a more user-friendly way to manage the database. I suggest Adminer which is a tool similar to phpMyAdmin.sudo apt install -y adminer

Roundcube

Roundcube is an email web interface.sudo apt install -y roundcube roundcube-plugins roundcube-plugins-extra roundcube-mysql

2. Preparing the Apache web server for HTTP

Let’s start with the web server. As an example, I will assume that you want to offer a host name webmail.example.org to your users. Of course, your server will have another name in a domain that you control. I will use that example throughout the tutorial though and keep that name printed in bold letters to remind you that you have to use your own host name.

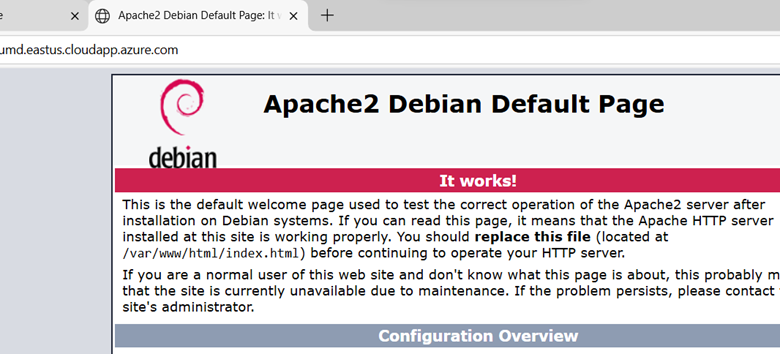

Do you just want to play around with your new server and not use an independent domain yet? No problem. Then you can set your DNS name label under Azure portal, which will create a subdomain for your website. If you have an independent domain then set up a DNS “A” and “AAAA” (if you use IPv6) record for that host name pointing to your server’s IP address.Open a web browser, and go to the DNS name of your website. You should see something like this:

First you need a web root directory for that host name:

sudo mkdir /var/www/webmail.example.org

sudo chown www-data:www-data /var/www/webmail.example.org

- /etc/apache2/sites-available/*.conf contains the actual configuration files for each virtual host. Putting a file here does not enable that host though. That’s done in the next step. There are two configuration files by default. “000-default.conf” is a HTTP virtual host and “default-ssl.conf” is a HTTPS virtual host.

- /etc/apache2/sites-enabled/*.conf contains symbolic links (“symlinks”) pointing to configuration files in the /etc/apache2/sites-available directory. Only *.conf links in this directory will be loaded by Apache.

You may remove the default symlinks in /etc/apache2/sites-enabled/* unless you use them already.

Create a new virtual host configuration file /etc/apache2/sites-available/webmail.example.org-http.conf and make it contain:

<VirtualHost *:80>

ServerName webmail.example.org

DocumentRoot /var/www/webmail.example.org

</VirtualHost>

Enable the site:

sudo a2ensite webmail.example.org-http

You will be told:

To activate the new configuration, you need to run:

systemctl reload apache2

You may need to add sudo at the beginning: sudo systemctl reload apache2

3. Getting a LetsEncrypt certificate

There are many ways to install letsencrypt certificate. The following way is the Linux (snapd) way:Install system dependencies

System dependency includes snapd:sudo apt update

sudo apt install snapd

Next, use the snap command to install the core snap. This will install some dependencies on your server that are needed for any snap you install, including the Certbot snap:

sudo snap install core

Then refresh the core snap. Doing so will ensure that you have the latest versions of snapd and its dependencies installed:sudo snap refresh core

Install Certbot

Note that snaps can be installed under one of three confinement levels which provide varying degrees of isolation from your system. For example, most snaps are installed under the --strict confinement level by default which prevents these programs from accessing your system’s files or network. Because Certbot must be allowed to edit certain configuration files in order to correctly set up certificates, this command includes the --classic option. This confinement level allows any snaps installed under it the same access to system resources as traditional packages.With this in mind, you can install the certbot snap with the following command.

sudo snap install --classic certbot

Prepare and run the Certbot command

This installation process will install the certbot executable in the /snap/bin/ directory. Create a symbolic link to this file in the /usr/bin/ directory to ensure that you can run the certbot command anywhere on your system:

sudo ln -s /snap/bin/certbot /usr/bin/certbot

Certbot provides a variety of ways to obtain SSL certificates through plugins. The Apache plugin will take care of reconfiguring Apache and reloading the configuration whenever necessary. To use this plugin, run the following:sudo certbot --apache -d your_domain -d www.your_domain -d anothername.com

This runs certbot with the --apache plugin, using -d to specify the names for which you’d like the certificate to be valid.If this is your first time running certbot, you will be prompted to enter an email address and agree to the terms of service. Additionally, it will ask if you’re willing to share your email address with the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a nonprofit organization that advocates for digital rights and is also the maker of Certbot. Feel free to enter Y to share your email address or N to decline.

After doing so, certbot will communicate with the Let’s Encrypt server, then run a challenge to verify that you control the domain you’re requesting a certificate for.If that’s successful, the configuration will be updated automatically and Apache will reload to pick up the new settings. certbot will wrap up with a message telling you the process was successful and where your certificates are stored:

Successfully received certificate.

Certificate is saved at: /etc/letsencrypt/live/umd.eastus.cloudapp.azure.com/fullchain.pem

Key is saved at: /etc/letsencrypt/live/umd.eastus.cloudapp.azure.com/privkey.pem

This certificate expires on 2025-09-18.

These files will be updated when the certificate renews.

Certbot has set up a scheduled task to automatically renew this certificate in the background.

Deploying certificate

Successfully deployed certificate for umd.eastus.cloudapp.azure.com to

/etc/apache2/sites-available/umd.eastus.cloudapp.azure.com-http-le-ssl.conf

Congratulations! You have successfully enabled HTTPS on https://umd.eastus.cloudapp.azure.com

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

If you like Certbot, please consider supporting our work by:

* Donating to ISRG / Let's Encrypt: https://letsencrypt.org/donate

* Donating to EFF: https://eff.org/donate-le

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Your certificates are downloaded, installed, and loaded. Try reloading your website using https:// and notice your browser’s security indicator. It should indicate that the site is properly secured, usually with a green lock icon. If you test your server using the SSL Labs Server Test, it will get an A grade.

Let’s finish by testing the renewal process.Verifying Certbot automatic renewal

Let’s Encrypt certificates are only valid for ninety days. This is to encourage users to automate their certificate renewal process. The certbot package you installed takes care of this for you by adding a renew script to /etc/cron.d. This script runs twice a day and will automatically renew any certificate that’s within thirty days of expiration.To test the renewal process, you can do a dry run with certbot:

sudo certbot renew --dry-run

If you receive no errors, you’re all set. When necessary, Certbot will renew your certificates and reload Apache to pick up the changes. If the automated renewal process ever fails, Let’s Encrypt will send a message to the email you specified, warning you when your certificate is about to expire.If you prefer to get the certificate only, refer to the ISPMail instruction as follows.

To get a certificate for your domain run:

sudo certbot certonly --webroot --webroot-path /var/www/webmail.example.org -d webmail.example.org

You can use multiple occurences of “-d” here to get a certificate valid for multiple domains. For example: “-d webmail.example.org -d something-else.example.org”. (See also: https://eff-certbot.readthedocs.io/en/stable/using.html#webroot) The first time you do that you will get asked for your email address so LetsEncrypt can send you reminders if your certificate would expire. You will also have to agree to their terms of service.

If everything worked well you should get output like:

Requesting a certificate for webmail.example.org

Successfully received certificate.

Certificate is saved at: /etc/letsencrypt/live/webmail.example.org/fullchain.pem

Key is saved at: /etc/letsencrypt/live/webmail.example.org/privkey.pem

This certificate expires on 2024-01-02.

These files will be updated when the certificate renews.

Certbot has set up a scheduled task to automatically renew this certificate in the background.

In /etc/letsencrypt/live/webmail.example.org you will find a couple of files now:

- cert.pem: the certificate file

- chain.pem: the chaining or intermediate certificate. This certificate provides information how the LetsEncrypt certificates are linked to other known certificate authorities. It is generally a good idea to always send this certificate along with your own for clients who may not know LetsEncrypt properly yet.

- fullchain.pem: this file contains a concatenation of the cert.pem and the chain.pem. This is the preferred file to use when a piece of software asks where to find the certificate.

- privkey.pem: the private key file. Keep it secret.

Make HTTPS default

You can enable HTTPS for your web server by default and redirect people to HTTPS even if they visit your website through HTTP. Create a new file /etc/apache2/sites-available/webmail.example.org-https.conf containing:

<VirtualHost *:443>

ServerName webmail.example.org

DocumentRoot /var/www/webmail.example.org

SSLEngine on

SSLCertificateFile /etc/letsencrypt/live/webmail.example.org/fullchain.pem

SSLCertificateKeyFile /etc/letsencrypt/live/webmail.example.org/privkey.pem

</VirtualHost>

Enable the SSL module in Apache:

sudo a2enmod ssl

Then enable the virtual host for HTTPS:sudo a2ensite webmail.example.org-https

And restart the web server. A reload is not sufficient this time because you added a module.sudo systemctl restart apache2

Redirect HTTP to HTTPS

Sometimes users forget to enter https://… when accessing your webmail service. So they access the HTTP web site. We obviously don’t want them to send their password over HTTP. So we should redirect all HTTP connections to HTTPS.One exception though. Let’s Encrypt will use HTTP to verify your challenge token. So we need to serve files at http://webmail.example.org/.well-known/acme-challenge/… directly while redirecting all other requests to HTTPS. You can accomplish that by putting these lines inside the <VirtualHost> section of your /etc/apache2/sites-available/webmail.example.org-http.conf file:

RewriteEngine On

RewriteCond %{REQUEST_URI} !.well-known/acme-challenge

RewriteRule ^(.*)$ https://%{SERVER_NAME}$1 [R=301,L]

sudo a2enmod rewrite

sudo systemctl restart apache2

4. Preparing the database

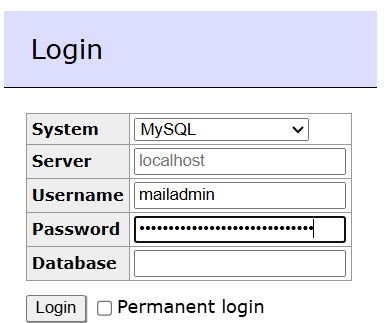

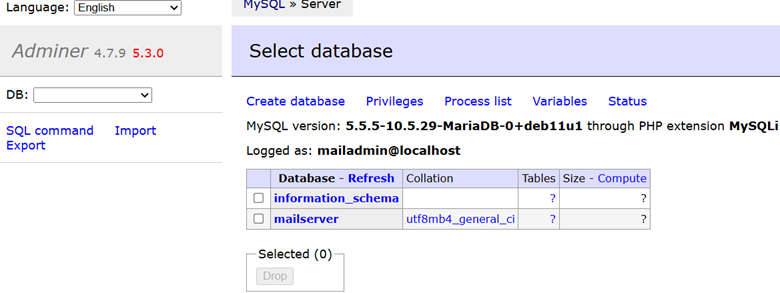

Now it’s time to prepare the MariaDB database that stores the information that controls your mail server. In the process you will have to enter SQL queries – the language of relational database servers. You may enter them in a terminal window using the ‘mysql’ command. But if you are less experienced with SQL you may prefer using a web interface. That’s what you installed Adminer for.Setting up Adminer

Basically, Adminer is just a couple of PHP files served from your Apache web server. The setup is simple. Edit your /etc/apache2/sites-available/webmail.example.org-https.conf file and put this line anywhere between the <VirtualHost> and the </VirtualHost> tags:Alias /adminer /usr/share/adminer/adminer

Reload the Apache process:systemctl reload apache2

Security warning

Having an SQL admin interface publicly available on your web site is an invitation for internet scoundrels to do bad things. Consider protecting the /adminer location by an additional password. The Apache documentation shows you how to do that. Or use a less obvious path than “/adminer” in the Alias.

You will not be able to login yet. The only available database user is ‘root’, but it is only usable from the shell by default – not over a network.Generate two random passwords

In this section you will create the basic database “mailserver” and two users. One user (“mailadmin”) will be able to change the data in the database and is meant for you. The other user (“mailserver”) can only read from the database and is meant for the server processes.

Use the pwgen tool to create two random passwords for these users:pwgen -s1 30 2

Take a note of the passwords or store them somewhere safe.Create the ‘mailserver’ database

This step is simple. Connect to the database using the ‘mysql’ command:sudo mysql

You should see the MariaDB prompt that allows you to enter further SQL commands:MariaDB [(none)]>

Now you are expected to speak SQL. To create a new database for our needs. Enter:CREATE DATABASE mailserver;

You will be told that your query was OK and that one new row was added.Create the database users

Now you have an empty database. Let us give the “mailadmin” database user the required privileges to manage it.You are still connected to the database, right? To create a user with full permissions enter this SQL command. Please use the first password you just generated instead of mine:

grant all privileges on mailserver.* to 'mailadmin'@'localhost' identified by 'E2zhrYD1156RtbPRgWLfU4uC0uCQ0g';

Also create the read-only user that will grant Postfix and Dovecot database access later (use your second random password here).

grant select on mailserver.* to 'mailserver'@'127.0.0.1' identified by 'uoDFE981mMpM0X996QNirfq4rJJ5ZR';

127.0.0.1 versus localhost

Wait a minute. Why is there “127.0.0.1” instead of “localhost” in the second SQL command? Is that a typo? No, it’s not. Well, in network terminology those two are identical. But MariaDB (and Oracle’s MySQL) distinguishes between the two. If you initiate a database connection to “localhost” then you talk to the socket file which lives at /var/run/mysqld/mysqld.sock on your server. But if you connect to “127.0.0.1” it will create a network connection talking to the TCP socket on port 3306 on your server. The difference is that any process on your server can talk to 127.0.0.1. But the socket file has certain user/group/other permissions just like any other file on your file system. Postfix will be restricted to its /var/spool/postfix directory and cannot by default access that socket file. So, by using 127.0.0.1 we circumvent that limitation.When you use Adminer you will have to use ‘localhost’ as a database server when using the ‘mailadmin’ user but ‘127.0.0.1’ when using the ‘mailserver’ user.

Now you can use Adminer to log in using the mailadmin account and the first password.

You should get logged in and see the “mailserver” database:

Creating the database tables

We need three Postfix mappings. One for virtual domains, one for virtual aliases and another for virtual users. Each of the mappings needs a database table that you will create now. Feel free to use Adminer. I will however show the SQL statement to create the tables that you can enter on the ‘mysql’ command-line tool. The first table to create is virtual_domains.This table just holds the list of domains that you will use as virtual_mailbox_domains in Postfix.

USE mailserver;

CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS `virtual_domains` (

`id` int(11) NOT NULL auto_increment,

`name` varchar(50) NOT NULL,

PRIMARY KEY (`id`)

) ENGINE=InnoDB DEFAULT CHARSET=utf8;

CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS `virtual_users` (

`id` int(11) NOT NULL auto_increment,

`domain_id` int(11) NOT NULL,

`email` varchar(100) NOT NULL,

`password` varchar(150) NOT NULL,

`quota` bigint(11) NOT NULL DEFAULT 0,

PRIMARY KEY (`id`),

UNIQUE KEY `email` (`email`),

FOREIGN KEY (domain_id) REFERENCES virtual_domains(id) ON DELETE CASCADE

) ENGINE=InnoDB DEFAULT CHARSET=utf8;

CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS `virtual_aliases` (

`id` int(11) NOT NULL auto_increment,

`domain_id` int(11) NOT NULL,

`source` varchar(100) NOT NULL,

`destination` varchar(100) NOT NULL,

PRIMARY KEY (`id`),

FOREIGN KEY (domain_id) REFERENCES virtual_domains(id) ON DELETE CASCADE

) ENGINE=InnoDB DEFAULT CHARSET=utf8;

Example data to play with

Too much theory so far? I can imagine. Let’s populate the database with an example.org domain, a john@example.org email account and a forwarding of jack@example.org to john@example.org. We will use that information in the next chapter to play with.To add that sample data just run these SQL queries:

USE mailserver;

REPLACE INTO virtual_domains (id,name) VALUES (1,'example.org');

REPLACE INTO virtual_users (id,domain_id,password,email)

VALUES (1, 1,

'{BLF-CRYPT}$2y$05$xAEZd6RSftRCRKWuGwbc4.2HR/RFI5JwMFpymE/.TWZXWUp1.Krqi',

'john@example.org');

REPLACE INTO virtual_aliases (id,domain_id,source,destination)

VALUES (1, 1, 'jack@example.org', 'john@example.org');

sudo doveadm pw -s BLF-CRYPT

…to create a secure hash of the simple password “summersun”. Once you have installed Dovecot you can try that yourself but you will get a different output. The reason is that the passwords are salted to increase their security.5. Let Postfix access MariaDB

In section 4, you have created the SQL database schema and inserted some data to play with. Let’s start with the entry point for all email on your system: Postfix. So, we need to tell Postfix how to get the information from the database. First let’s tell it how to find out if a certain domain is a valid email domain.virtual_mailbox_domains

A mapping in Postfix is just a table that contains a left-hand side (LHS) and a right-hand side (RHS). To make Postfix get information about virtual domains from the database we need to create a ‘cf’ file (configuration file). Start by creating a file called /etc/postfix/mysql-virtual-mailbox-domains.cf for the virtual_mailbox_domains mapping. Make it contain:

user = mailserver

password = uoDFE981mMpM0X996QNirfq4rJJ5ZR

hosts = 127.0.0.1

dbname = mailserver

query = SELECT 1 FROM virtual_domains WHERE name=‘%s’

Imagine that Postfix receives an email for somebody@example.org and wants to find out if example.org is a virtual mailbox domain. It will run the above SQL query and replace ‘%s’ by ‘example.org’. If it finds such a row in the virtual_domains table it will return a ‘1’. Actually, it does not matter what exactly is returns as long as there is a result. Remember the puppies and kittens?

Now you need to make Postfix use this database mapping:sudo postconf virtual_mailbox_domains=mysql:/etc/postfix/mysql-virtual-mailbox-domains.cf

The “postconf” command conveniently adds configuration lines to your /etc/postfix/main.cf file. It also activates the new setting instantly so you do not have to reload the Postfix process.The test data you created earlier added the domain “example.org” as one of your mailbox domains. Let’s ask Postfix if it recognizes that domain:

sudo postmap -q example.org mysql:/etc/postfix/mysql-virtual-mailbox-domains.cf

You should get ‘1’ as a result. That means your first mapping is working. Feel free to try that with other domains after the -q in that line. You should not get a response.You will now define the virtual_mailbox_maps. It will map a recipient’s email address (left-hand side) to the location of the user’s mailbox on your hard disk (right-hand side). Postfix has a built-in transport service called “virtual” that can receive the email and store it into the recipient’s email directory. That service is pretty limited, so we will delegate that to Dovecot as it allows us better control.

Postfix will forward all emails to Dovecot for further delivery. But we need to make sure that the recipient actually exists before we do that. So, Postfix needs to check whether an email address belongs to a valid mailbox. That simplifies things a bit because we just need the left-hand side of the mapping.Similar to the above virtual_domains mapping you need an SQL query that searches for an email address and returns “1” if it is found.

To accomplish that please create another configuration file at /etc/postfix/mysql-virtual-mailbox-maps.cf:user = mailserver

password = uoDFE981mMpM0X996QNirfq4rJJ5ZR

hosts = 127.0.0.1

dbname = mailserver

query = SELECT 1 FROM virtual_users WHERE email=‘%s’

Tell Postfix that this mapping file is supposed to be used for the virtual_mailbox_maps mapping:

sudo postconf virtual_mailbox_maps=mysql:/etc/postfix/mysql-virtual-mailbox-maps.cf

Test if Postfix is happy with this mapping by asking it where the mailbox directory of our john@example.org user would be 1:sudo postmap -q john@example.org mysql:/etc/postfix/mysql-virtual-mailbox-maps.cf

virtual_alias_maps

The virtual_alias_maps mapping is used for forwarding emails from one email address to one or more others. In the database multiple targets are achieved by using multiple rows.Create another “.cf” file at /etc/postfix/mysql-virtual-alias-maps.cf:

user = mailserver

password = uoDFE981mMpM0X996QNirfq4rJJ5ZR

hosts = 127.0.0.1

dbname = mailserver

query = SELECT destination FROM virtual_aliases WHERE source=‘%s’

Make Postfix use this database mapping:

sudo postconf virtual_alias_maps=mysql:/etc/postfix/mysql-virtual-alias-maps.cf

Test if the mapping file works as expected:sudo postmap -q jack@example.org mysql:/etc/postfix/mysql-virtual-alias-maps.cf

You should see the expected destination:john@example.org

6. Catch-all aliases

This section is entirely optional and will not affect your mail server if you skip it.As explained earlier in the tutorial there is way to forward all email addresses in a domain to a certain destination email address. This is called a catch-all alias. Those aliases catch all emails for a domain if there is no specific virtual user for that email address. Catchalls are considered a bad idea. It is tempting to generally forward all email addresses to one person if e.g., your marketing department requests a new email alias every week. But the drawback is that you will get more spam because spammers will send their stuff to any address of your domain. Or perhaps a sender mixed up the proper spelling of a recipient but the mail server will forward the email instead of rejecting it for a good reason. So, think twice before using catchalls.

You still want to use catch-all addresses? Well, okay. Let’s do it then. A catchall alias looks like “@example.org” and forwards email for the whole domain to other addresses. We have created the john@example.org user and would like to forward all other email on the domain to kerstin@example.com. So, we would add a catchall alias like:

| Source | Destination |

|---|---|

| @example.org | kerstin@example.com |

But there is a small catch. Postfix always checks the virtual_alias_maps mapping before looking up a user in the virtual_mailbox_maps. Imagine what happens when Postfix receives an email for ‘john@example.org’. Postfix checks the aliases in the virtual_alias_maps table. It finds the catchall entry as above and since there is no more specific alias the catchall account matches and the email is redirected to ‘kerstin@example.com’.

In other words: the aliases are always processed first. So, a catch-all alias will steal the email. John will never get any email. This is not what you want.But imagine that the aliases would contain a second entry like this:

| destination | |

|---|---|

| @example.org | kerstin@example.com |

| john@example.org | john@example.org |

So, any email address on the example.org domain will be forwarded to kerstin’s address. But what is that second line? Why should we forward john’s emails to himself? That doesn’t make any sense.

Actually, it does. Postfix will consider more specific aliases first. And john@example.org is more specific than @example.org. Consider that someone is trying to reach john@example.org’s mailbox. If Postfix read this table just from top to bottom, then it would see @example.org first, which would be a match. It would then redirect that email to kerstin. John would never again get an email.

So, to make a mixture of catch-all addresses and specific addresses work, we need this little trickery.Postfix will lookup all these mappings for each of:

- john@example.org (most specific)

- @example.org (catchall – least specific)

We do not want to add that “more specific” entry for each email address manually. Fortunately, we can easily automate that. For that “john-to-himself” mapping you need to create another “.cf” file /etc/postfix/mysql-email2email.cf for the latter mapping:

user = mailserver

password = x893dNj4stkHy1MKQq0USWBaX4ZZdq

hosts = 127.0.0.1

dbname = mailserver

query = SELECT email FROM virtual_users WHERE email=‘%s’

sudo postmap -q john@example.org mysql:/etc/postfix/mysql-email2email.cf

The result should be the same address:john@example.org

Now you need to tell Postfix that it should check both the aliases and the “john-to-himself”:sudo postconf virtual_alias_maps=mysql:/etc/postfix/mysql-virtual-alias-maps.cf,mysql:/etc/postfix/mysql-email2email.cf

The order of the two mappings is not important here. Postfix will check all ‘cf’ files anyway and merges what it finds.You did it! All mappings are set up and the database is generally ready to be filled with domains and users. Make sure that only ‘root’ and the ‘postfix’ user can read the “.cf” files – after all your database password is stored there:

sudo chgrp postfix /etc/postfix/mysql-*.cf

sudo chmod u=rw,g=r,o= /etc/postfix/mysql-*.cf

7. Setting up Dovecot

This section of our journey leads us to Dovecot – the software that…- gets emails destined to your users from Postfix and saves them to disk

- executes user-based sieve filter rules (can be used to e.g., move emails to different folders based on certain criteria or to send automated vacation responses)

- allows the user to fetch emails using POP3 or IMAP

sudo groupadd -g 5000 vmail

sudo useradd -g vmail -u 5000 vmail -d /var/vmail -m

!include conf.d/*.conf

It loads all files in /etc/dovecot/conf.d/ that end in “.conf” in alphanumerical order. So “10-auth.conf” is loaded first and “90-sieve-extprograms.conf” is loaded last. The big advantage is that you can edit or replace parts of the configuration without having to overwrite the entire configuration. The main /etc/dovecot/dovecot.conf file does not require any changes. Those other files in conf.d/ however do.conf.d/10-auth.conf

The most common authentication mechanism is called PLAIN. However, if you have Outl**k users then you may need to add the LOGIN mechanism, too.:auth_mechanisms = plain login

These two mechanisms would ask for a password without enforcing encryption to secure the password. But don’t worry. By default, Dovecot sets disable_plaintext_auth = yes which ensures that authentication is only accepted over TLS-encrypted connections.At the end of this file, you will find various authentication backends that Dovecot ships with. By default, it will use system users (those from the /etc/passwd). But we want to use the MariaDB database backend so go ahead and change this block to:

#!include auth-system.conf.ext

!include auth-sql.conf.ext

#!include auth-ldap.conf.ext

#!include auth-passwdfile.conf.ext

#!include auth-checkpassword.conf.ext

#!include auth-static.conf.ext

10-mail.conf

Change the mail_location setting to:mail_location = maildir:~/Maildir

This is the directory where Dovecot will look for the emails of a specific user. The tilde character (~) means the user’s home directory. That does not make sense yet. But further down on this page we will tell Dovecot what the home directory is supposed to mean. For example, john@example.org will have his home directory in /var/vmail/example.org/john.Further down in the 10-mail.conf file you will find sections defining the namespaces. Those are folder structures that your email program sees when connecting to the mail server. If you use POP3 you can only access the “inbox” – which is where all incoming email is stored. Using the IMAP protocol, you get access to a hierarchy of folders and subfolders. And you can even share folders between users. Or use a public folder that can be accessed by anyone – even anonymously. So, IMAP is generally to be preferred.

Also edit the “mail_plugins” line to enable the quota plugin we will configure later and turn it into:mail_plugins = quota

10-master.conf

This configuration file deals with typical service ports like IMAP or POP3.So, most settings are sane here and do not have to be changed. However, one change is required in the “service auth” section because we want Postfix to allow Dovecot as an authentication service. Make it look like this:

# Postfix smtp-auth

unix_listener /var/spool/postfix/private/auth {

mode = 0660

user = postfix

group = postfix

}

Well, Postfix runs in a chroot environment located at /var/spool/postfix. It can’t access anything outside of that directory. So, to allow communication with Postfix we tell Dovecot to place a communication socket into that chroot.

10-ssl.conf

You created both a key and a certificate file to encrypt the communication with POP3, IMAPs and HTTPS between the users and your mail server. You need to tell Dovecot where to find these files:ssl_cert = </etc/letsencrypt/live/webmail.example.org/fullchain.pem

ssl_key = </etc/letsencrypt/live/webmail.example.org/privkey.pem

ssl = required

Next let’s take a look at how Dovecot knows about users and their passwords:auth-sql.conf.ext

Dovecot reads the auth-sql.conf.ext which defines how to find user information in your database. Open the file. There are two sections:- userdb: where to find a user’s mailbox in the file system

- passdb: where to find the user’s hashed password

The “userdb” section already reads:

userdb {

driver = sql

args = /etc/dovecot/dovecot-sql.conf.ext

}

As you can see Dovecot uses an SQL database lookup to get that information. And it refers to the dovecot-sql.conf.ext file for more information. Let’s see…

/etc/dovecot/dovecot-sql.conf.ext

(This configuration file is one level up and not in “conf.d”.)You will find this file well documented although all configuration directives are commented out. Add these lines at the bottom of the file:

driver = mysql

connect = \

host=127.0.0.1 \

dbname=mailserver \

user=mailserver \

password=uoDFE981mMpM0X996QNirfq4rJJ5ZR

user_query = SELECT email as user, ‘/var/vmail/%d/%n’ As home, 5000 AS uid, 5000 AS gid FROM virtual_users WHERE email=‘%u’

password_query = SELECT password FROM virtual_users WHERE email=‘%u’

Backslashes

Ending a line with a backslash () means that it is continued on the next line. It keeps the configuration more readable when it is split over multiple lines.What these lines mean:

- driver: the kind of database. MariaDB is the same kind as MySQL.

- connect: where to find the MySQL database and how to access it (username, password)

- user_query: an SQL query that returns the user name (=the email address), the quota, the home directory, user ID and group ID.

- password_query: this SQL query just gets the password hash from the database

- email AS user

It gets the email field from the database which corresponds to the user name. Dovecot expects it in the user field so we set an alias to “user”. - userdb_home

This leads to the directory where all emails and various control files for this user are located. The placeholder ‘%d’ replaces the domain and ‘%n’ the user part. So, for John that makes it “/var/vmail/example.org/john”. - userdb_uid and userdb_gid

Those are the user ID and group ID of vmail user – 5000 for both. Dovecot uses it to set the permissions of files it creates. As all users share the same system user “vmail” this is just a static number.

Fix permissions

Make sure that only root can access the SQL configuration file so nobody else is reading your database access passwords:sudo chown root:root /etc/dovecot/dovecot-sql.conf.ext

sudo chmod go= /etc/dovecot/dovecot-sql.conf.ext

sudo systemctl restart dovecot

Look at your /var/log/mail.log logfile. You should see:... Dovecot v2.3.13 (89f716dc2) starting up for imap, lmtp, sieve, pop3 (core dumps disabled)

If you get any error messages, please double-check your configuration files.8. Let Postfix send emails to Dovecot

I hope you haven’t lost your mind yet.In Section 7, we make sure that Postfix knows which emails it is allowed to receive. Now what to do with the email? It has to be saved to disk into the mailbox of the mail user who is eagerly waiting for it. You could let Postfix handle that using its built-in mail delivery agent (MDA) called “virtual“. However, compared to the capabilities that Dovecot provides like server-based sieve rules or quotas the Postfix delivery agent is pretty basic. We are using Dovecot anyway to provide the IMAP (and optionally POP3) service. So, let’s use its delivery agent.

How can we make Postfix hand over the email to Dovecot? There are generally two ways to establish that link.- Using the dovecot-lda (local delivery agent) process. It can process one email at a time. And it starts up a new process for every email. This was for long the default way. But as you can imagine that it does not scale well.

- The better option is to use LMTP (local mail transport protocol) that was conceived for this purpose. It can handle multiple recipients at the same time and has a permanently running process which provides a better performance than using the LDA. In short, LMTP is a variant of SMTP with fewer features. It is meant for email communication between internal services that trust each other.

You guessed it already – we will go for the second option. You installed the dovecot-lmtpd package earlier. So, let’s configure it.

Tell Dovecot where to listen for LMTP connections from Postfix

Edit Dovecot’s configuration file that deals with the LMTP daemon – you can find it at /etc/dovecot/conf.d/10-master.conf. Look for the “service lmtp” section and edit it so that it looks like:

service lmtp {

unix_listener /var/spool/postfix/private/dovecot-lmtp {

group = postfix

mode = 0600

user = postfix

}

}

This makes Dovecot’s lmtp daemon create a UNIX socket at /var/spool/postfix/private/dovecot-lmtp. Just like in the section dealing with setting up Dovecot we make it put a socket into the /var/spool/postfix chroot directory because Postfix is restricted to that directory and cannot access anything outside of it. So from Postfix’s point of view the socket is located at “/private/dovecot-lmtp”.

Restart Dovecot…

sudo systemctl restart dovecot

Check if dovecot accepted that change:systemctl status dovecot

The output should contain “Active: active (running)”.Tell Postfix to deliver emails to Dovecot using LMTP

This is even easier. The “virtual_transport” in Postfix defines the service to use for delivering emails to the local system. Dovecot has created a socket file and is ready to listen to incoming LMTP connections. We just need to tell Postfix to send emails there:sudo postconf virtual_transport=lmtp:unix:private/dovecot-lmtp

The syntax looks crazy, but it’s actually simple. You just told Postfix to use the LMTP protocol. And that we want to use a UNIX socket on the same system (instead of a TCP connection). And the socket file is located at /var/spool/postfix/private/dovecot-lmtp.Enable server-side mail rules

One of my favorite features of Dovecot are automatic rules for incoming email that are processed on the server. You can sort away your mailing list emails into special folders. You can reject certain senders. Or you can set up vacation auto-responders. No need to have a mail client running – it all happens automatically on the server even when your mail users are not connected.The open standard (RFC 5228) for such rules is called Sieve. Basically, Sieve is a way to manage server-side email rules. A rule consists of conditions and actions. For example, if the sender address matches steve@example.org you could tell Dovecot to move such emails to your “steve” folder automatically. These rules are stored on the Dovecot server and executed automatically. Whether you connect from your smartphone your laptop or use the webmail access – the rules always work and require no configuration on the client side.

As we use LMTP that’s where we need to tell the lmtp service that we want to use Dovecot’s “sieve” plugin. Edit the file /etc/dovecot/conf.d/20-lmtp.conf and within the “protocol lmtp” section change the “mail_plugins” line to:mail_plugins = $mail_plugins sieve

Restart Dovecot and you are done:sudo systemctl restart dovecot

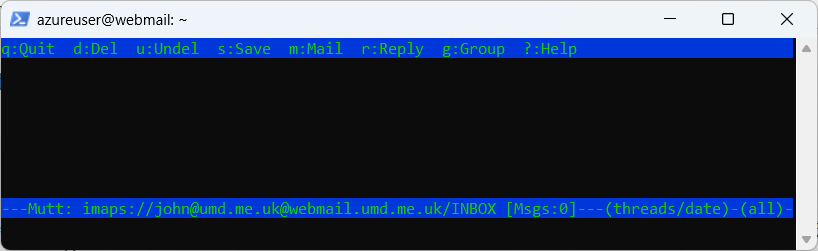

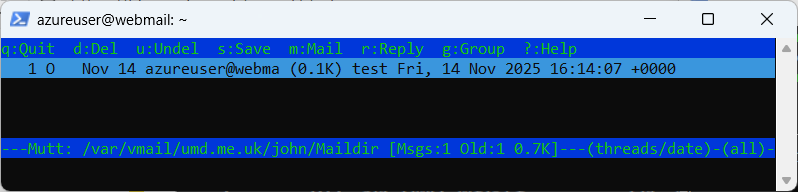

9. Testing IMAP

You have already completed the configuration of Dovecot. So, fetching emails via IMAP should already work. Let’s give it a try using a simple-looking but powerful IMAP client: mutt.

mutt -f imaps://john@example.org@**webmail.example.org**

The connection URL may look a little confusing because of the two “@” characters. Usually, mutt expects the format imaps://user@server. And as we use the email address as the “user” part you get this look.You should get prompted for the password which we set to “summersun”.

If you get any certificate warnings then check if you used the correct server name to connect to and if you completed the certificate/LetsEncrypt part earlier in this guide.After logging in you will see an empty inbox:

10. Testing email delivery

So far you have spent considerable time with theory and configuration. Are you worried whether all you did actually leads to a working mail server? Before we do the final steps let’s take a break and verify that everything you did so far works as expected.At this point the /var/vmail directory should be empty or maybe contain an “example.org” directory if you played with the john@example.org account previously. You can get a list of all files and directories within by running:

sudo find /var/vmail

Although there are not actually any emails on the server yet, you may still get something along the lines of:/var/vmail

/var/vmail/.profile

/var/vmail/.bash_logout

/var/vmail/4.213.182.137.nip.io

/var/vmail/4.213.182.137.nip.io/john

/var/vmail/4.213.182.137.nip.io/john/Maildir

/var/vmail/4.213.182.137.nip.io/john/Maildir/cur

/var/vmail/4.213.182.137.nip.io/john/Maildir/tmp

/var/vmail/4.213.182.137.nip.io/john/Maildir/dovecot.list.index.log

/var/vmail/4.213.182.137.nip.io/john/Maildir/dovecot.index.log

/var/vmail/4.213.182.137.nip.io/john/Maildir/new

/var/vmail/4.213.182.137.nip.io/john/Maildir/dovecot-uidlist

/var/vmail/4.213.182.137.nip.io/john/Maildir/maildirfolder

/var/vmail/4.213.182.137.nip.io/john/Maildir/dovecot-uidvalidity

/var/vmail/4.213.182.137.nip.io/john/Maildir/dovecot-uidvalidity.6852ff0a

Each IMAP mail folder has three subdirectories:

- new – every file here is an email that was stored in this mail folder but not yet read

- cur – the same but for email that has been read already

- tmp – for temporary files from the mail server

- …/Maildir/new/… – the main inbox

- …/Maildir/.INBOX.reddit/new/… – the “reddit” mail folder below the inbox

- …/Maildir/.INBOX.servers.inga/new/… – the “servers”/”inga” mail folder below the inbox

Check Postfix

To check for obvious configuration error in Postfix please run:sudo postfix check

Send a test email

It is time to send a new email into the system. Open a new terminal window and run

tail -f /var/log/mail.log

to see what the mail server is doing. Now let’s send an email to John. My favorite tool for mail tests is swaks that you installed earlier. In the original terminal run:swaks --to john@example.org --server localhost

If all works as expected, your mail.log will show a lot of technical information about the email delivery. Let me explain what happens at each stage.- postfix/smtpd[717234]: connect from localhost[::1]

Postfix receives an incoming SMTP connection. - postfix/smtpd[717234]: 6CCBB120268: client=localhost[::1]

Postfix assigns a unique identifier (6CCBB120268) to this connection so that you see which log lines belong together. This is especially important with busy mail servers where multiple mails are handled in parallel. - postfix/cleanup[717245]: 6CCBB120268: message-id=<20251109120838.717233@webmail.example.org>

swaks created a unique message id to the email which helps you identify specific mails in the log file. - postfix/qmgr[1437]: 6CCBB120268: from=<azureuser@webmail.example.org>, size=462, nrcpt=1 (queue active)

The sender was azureuser@webmail.example.org. This is logged after swaks sent the “MAIL FROM” line during the SMTP dialog. - postfix/smtpd[717234]: disconnect from localhost[::1] ehlo=1 mail=1 rcpt=1 data=1 quit=1 commands=5

The SMTP communication ends. Postfix has received and queued the email. - dovecot: lmtp(717249): Connect from local

Postfix connects to Dovecot to hand over the email via the LMTP interface. - dovecot: lmtp(john@example.org)<717249><+c0rHUaEEGnB8QoATRJD4g>: sieve: msgid=<20251109120838.717233@webmail.example.org>: stored mail into mailbox 'INBOX'

Dovecot received the email and stored his mailbox. - postfix/lmtp[717248]: 6CCBB120268: to=<john@example.org>, relay=webmail.example.org[private/dovecot-lmtp], delay=0.1, delays=0.03/0.01/0.02/0.05, dsn=2.0.0, status=sent (250 2.0.0 <john@example.org> +c0rHUaEEGnB8QoATRJD4g Saved)

This is the one of the most interesting lines in your mail log. It tells you what happened with a certain email. In this case it says that it was handed over to dovecot-lmtp and that the delivery was successful (status=sent). The status codes like 2.0.0 are defined in RFC 3463 and work similar to status codes in HTTP. Codes beginning with ‘2’ are good. Those with ‘4’ are temporary errors. And ‘5’ stands for a permanent failure. - dovecot: lmtp(717249): Disconnect from local: Client has quit the connection (state=READY)

The LMTP connection between Postfix and Dovecot is closed.

Look again:

sudo find /var/vmail/example.org/johnYou can also use a slightly more comfortable tool to access Maildirs that will come handy for you as a mail server administrator: “mutt”.

sudo mutt -f /var/vmail/example.org/john/Maildir

(You may get asked to create /root/Mail – this is standard procedure. Just press Enter.)

What you see now are the contents of John’s mailbox:

Using mutt is a nice way to check mailboxes while you are logged in to the mail server.

To reiterate what happens when you receive an email:- Postfix receives the email (using the “swaks” command in this example – but usually through the network using the SMTP protocol from other servers)

- Postfix asks Dovecot if the user is over quota

- Postfix talks to Dovecot via LMTP and hands over the email

- Dovecot runs through the user’s Sieve rules

- Dovecot writes the email file to disk

The first part of this tutorial covers how to set up mail server to receive email. Follow the following instruction “A mail server to send email” regarding how to config the mail server to send email.